BAN ON RICE

EXPORTS SHAKES BUSINESS LANDSCAPE

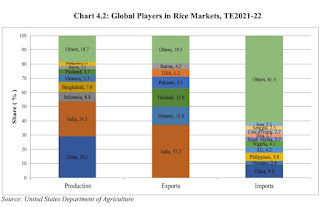

In a surprising turn of events,

the Government's decision to impose a prohibition on the export of seven

million tons of rice has reverberated through the global market. This move is

expected to trigger an abnormal increase in rice and wheat prices worldwide.

The Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) issued a notification on July

20, 2023, announcing the ban on various non-basmati rice varieties. This

decision has sent shockwaves across the Indian rice export industry and has

caught the attention of importing nations worldwide.

However, the rationale behind

this decision seems puzzling, given the publicly available data on rice

production. It remains unclear what privileged information the Government possesses

that has not been shared with the public or the exporting community.

According to the latest report

from the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) on the Kharif

crop, rice production is projected to reach approximately 131 million tonnes.

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) estimates the total rice supply to be

around 40.6 million tonnes as of July 1, 2023, surpassing the stocking norms of

13.54 million tonnes for the Central Pool. This surplus stock could lead to

higher storage and financing costs, ultimately resulting in increased food

subsidy expenditures.

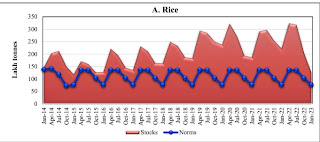

Interestingly, the root cause of

this prohibition may not be a shortage of rice but rather a downward trend in

surplus stocks of wheat. Graphs depicting the availability of rice and wheat

stocks in comparison to buffer norms could provide insight into the motivation

behind the ban. Speculatively, the Government may be aiming to preserve rice as

a potential substitute for wheat during periods of wheat scarcity.

The announcement of this

prohibition has already triggered a substantial increase in the prices of

various rice grades, with Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar experiencing a surge

of $50 to $100 per metric ton. This trend is anticipated to continue in the

near future. Notably, India's previous ban on Non-Basmati Rice exports in April

2008 catapulted international rice prices to a staggering $1000 per metric ton

fob, a surge that only subsided in September 2011 when the prohibition was

lifted. The recent International Grain Council graphic indicates a price

escalation of about 50% in Thai and Vietnam values of rice. Indian quotes are unavailable for obvious reasons.

The associated costs could be considerably elevated if India is compelled to import wheat with reduced duties, whether through private channels or other means. The volatility in US SRW wheat values is equally more than 50%.

Consequently, the ban on NBR

should not be regarded as a viable strategy to address the potential

speculative scarcity of wheat. The fundamental question arises: why impose

punitive measures on rice and rice exporters due to speculative concerns?

Factors like El Nino and unexpected rainfall patterns during the Rabi season

are acts of nature beyond prediction. While it is advisable to exercise

caution, it is equally important not to undermine the existing economic

activities through such measures.

MAJOR RICE EXPORTING

NATIONS (QTY IN 000 METRIC TONS )

THE PRIMARY RICE-PRODUCING STATES IN INDIA

India boasts 11 significant rice-producing

states, namely Punjab, Haryana, Odisha, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Telangana,

Uttarakhand, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh.

This collective effort ensures a consistent abundance of rice within the

nation. Despite wheat cultivation being concentrated in Punjab, Haryana,

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh, the substantial surplus of

rice raises questions about the rationale behind the current ban. Instead, this

ban could potentially convey a message of wheat hoarding within trade circles,

thereby inducing inflationary pressures.

ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES OF THE

BAN:

|

1.

Loss of approximately 7 million tons of white

rice in export volume. |

|

2.

Foregone foreign exchange earnings amounting

to nearly $3 billion. |

|

3.

Erosion of reputation among foreign markets

established by Indian rice exporters. |

|

4.

Diminished investments due to stock holdings

by exporters in key port towns like Vizag, Kakinada, and Kandla. |

|

5.

Financial strain on committed millers in

Chhattisgarh, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh, impacting export-oriented

production and the realization of premium prices. This, in turn, could lead

to repercussions across labor-intensive sectors such as packaging,

transportation, and warehousing. |

REMEDIAL SUGGESTIONS

Throughout the span of a decade

or even longer, Indian exporters have taken significant leaps forward in

advancing the reputation of non-basmati rice originating from India,

particularly within African markets and extending beyond. A considerable number

among them have effectively introduced their own distinctive brands and have

set up well-organized warehousing infrastructures across diverse African

nations. Abruptly halting rice exports could potentially undermine the

extensive effort invested over the years, providing an opportunity for our

rivals to regain the influential position that Indian exporters have

assiduously nurtured.

1. Preserving Export Continuity:

A prudent step forward entails maintaining a certain level

of export continuity, demonstrating a balanced approach to potential supply

concerns.

2. Alternative Measures for Supply Assurance:

Considering persistent worries about supply shortages, the Government

could explore alternatives such as quantitative or qualitative restrictions,

instead of an outright ban.

3. Safeguarding Premium Exports:

Preserving the export of premium-grade rice protects the

substantial investments made by exporters in branding and packaging, preventing

irrevocable losses.

4. Setting Minimum Export Price:

Aligning with international rates for premium rice

varieties, a minimum export price akin to major competitors like Thailand and

Vietnam could offer a viable resolution.

5. Controlled Distribution via Open Tender:

A controlled strategy could involve imposing quantitative

restrictions and allowing limited exports through an open tender or bidding

process.

6. Inclusive Participation and Allocation:

Enabling all exporters to participate and bid for specific

quantities, with set parameters like a minimum lot size of 5000 metric tons and

a maximum of 50000 metric tons per trader.

7. Prioritizing Highest Bidders:

Allocation of distribution to the highest bidders in

descending order, aligning with their bid quantities.

8. A Balanced Approach for Progress:

In conclusion, recognizing the validity of the Government's

concerns, a blanket ban on non-basmati white rice exports may counteract

progress achieved over the years by Indian exporters.

9. Consideration for All Stakeholders:

Embracing a more balanced and controlled approach, taking into account the investments and endeavors of exporters, could lead to a more favorable outcome for all stakeholders.